- News

Chinese New Year, the most significant annual holiday for the approximately 1.5 billion Chinese worldwide, began this week. Also known as Lunar New Year, it follows the phases of the moon. In contrast, the western calendar tracks the orbit of the sun. This is why the date varies year to year but usually falls between 21 January – 20 February.

At a glance

- Chinese New Year 2026 is Year of the Horse

- SJP has put together some charts and comments on aspects of the economy

- Broad based stand alone and comparative based

Chinese New Year follows a 12-year cycle with each year associated with a particular animal. 2026 is the Year of the Horse. This is associated with people born in 1966, 1978, 1990, 2002 and 2026.

People born during the Year of the Horse are identified with the following characteristics:

Strengths: Generous, good communicators, friendly with a positive attitude.

Weaknesses: Love to spend but not so good at saving. They can’t keep secrets and may be vain.

Relationships: Sentimental and emotional but with realistic attitudes towards relationships. Best matches are with people born in the year of the Tiger,

Sheep or Rabbit. Bad matches are with a Rat, Ox or Rooster.

Life and career: Often rebellious in their youth, Horse personalities often thrive, helped by their outgoing character. Prefer giving orders to obeying them.

To mark the Year of the Horse, we have selected some charts reflecting various aspects of China’s economy.

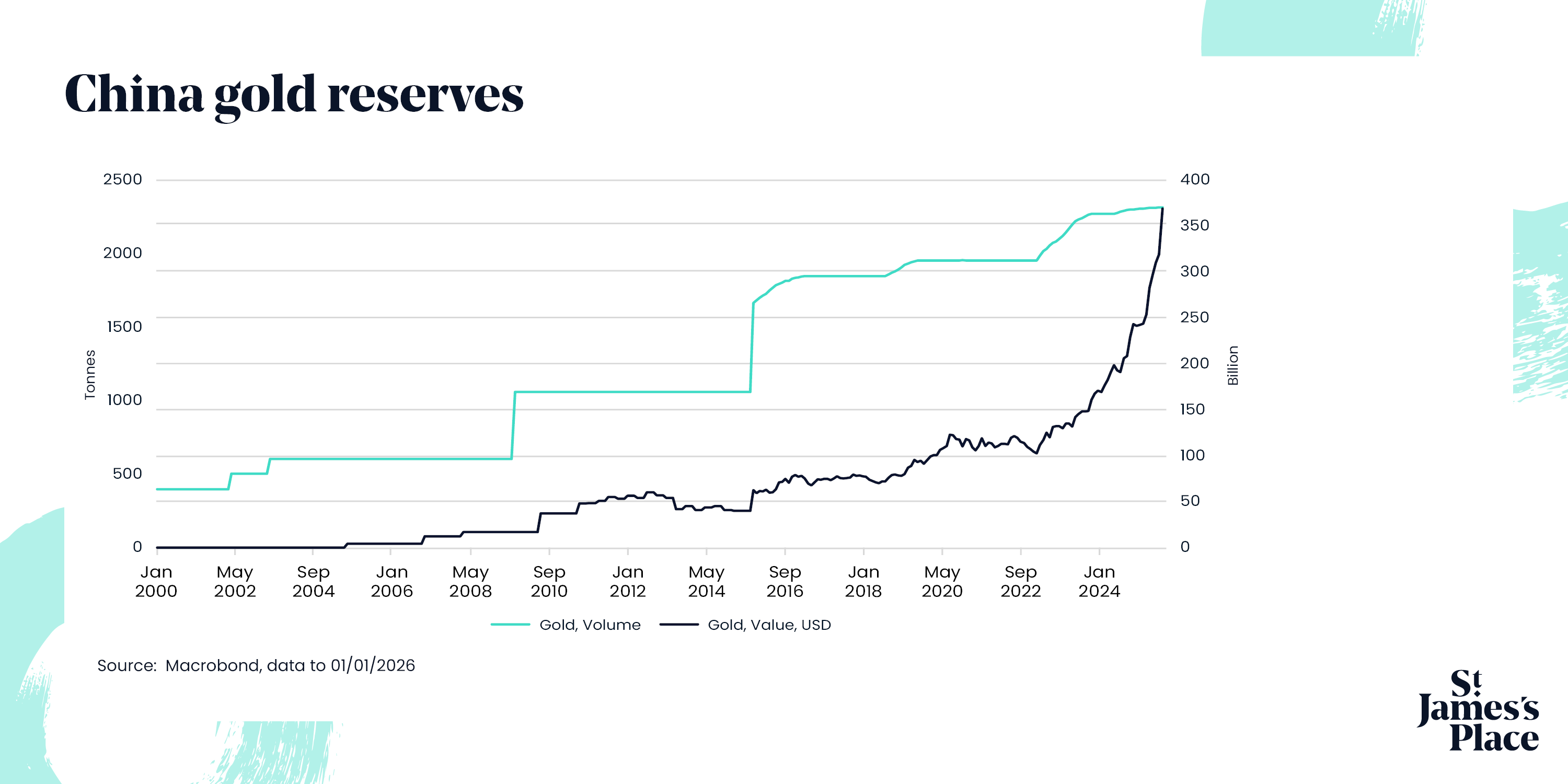

Gold holdings accelerated post 20221

- Governments around the world took note when the G7 group of industrial nations and the European Union used their influence to freeze Russian assets following its invasion of Ukraine in early 2022.

- China responded by accelerating its diversification away from US dollar denominated assets (“de-dollarisation”). It has since been buying more gold. Held domestically or in a ‘friendly’ depositary, gold carries no counterparty risk. This means it cannot be seized or cancelled. China’s gold purchasing policy follows in the wake of its longer-term sell-down of US treasury bonds and US dollar holdings.

- Accounting for more than half of all global reserves, the US dollar is expected to remain the most popular global reserve currency. However, China’s leadership has recently reiterated its aim for the yuan to become an alternative to the dollar.

- By increasing its gold holdings, it helps the Chinese government underpin confidence in the Chinese yuan. This comes at a time when President Trump has called for a weaker US dollar, western governments struggle with high levels of debts and geopolitical tensions are on the rise.

The multi-year residential property downturn2

- Entering its sixth year, the main catalyst for the downturn in Chinese residential property prices was (in hindsight) self-inflicted. In 2020, the government created regulations aimed at reducing a debt-fuelled bubble in the property sector.

- The effect was to greatly reduce borrowings to property developers, causing the high-profile collapse of heavily indebted developers.

- Investing in property had accounted for the bulk of household wealth in China. The prolonged downturn is causing people to rethink the traditional “only way is up” consumer mindset.

- Many potential homebuyers remain on the sidelines. Consumer sentiment is weak, and there are still high levels of unsold residential units. Memories of the government’s intervention remain fresh, as is the government’s slogan that “houses are for living, not for speculation”.

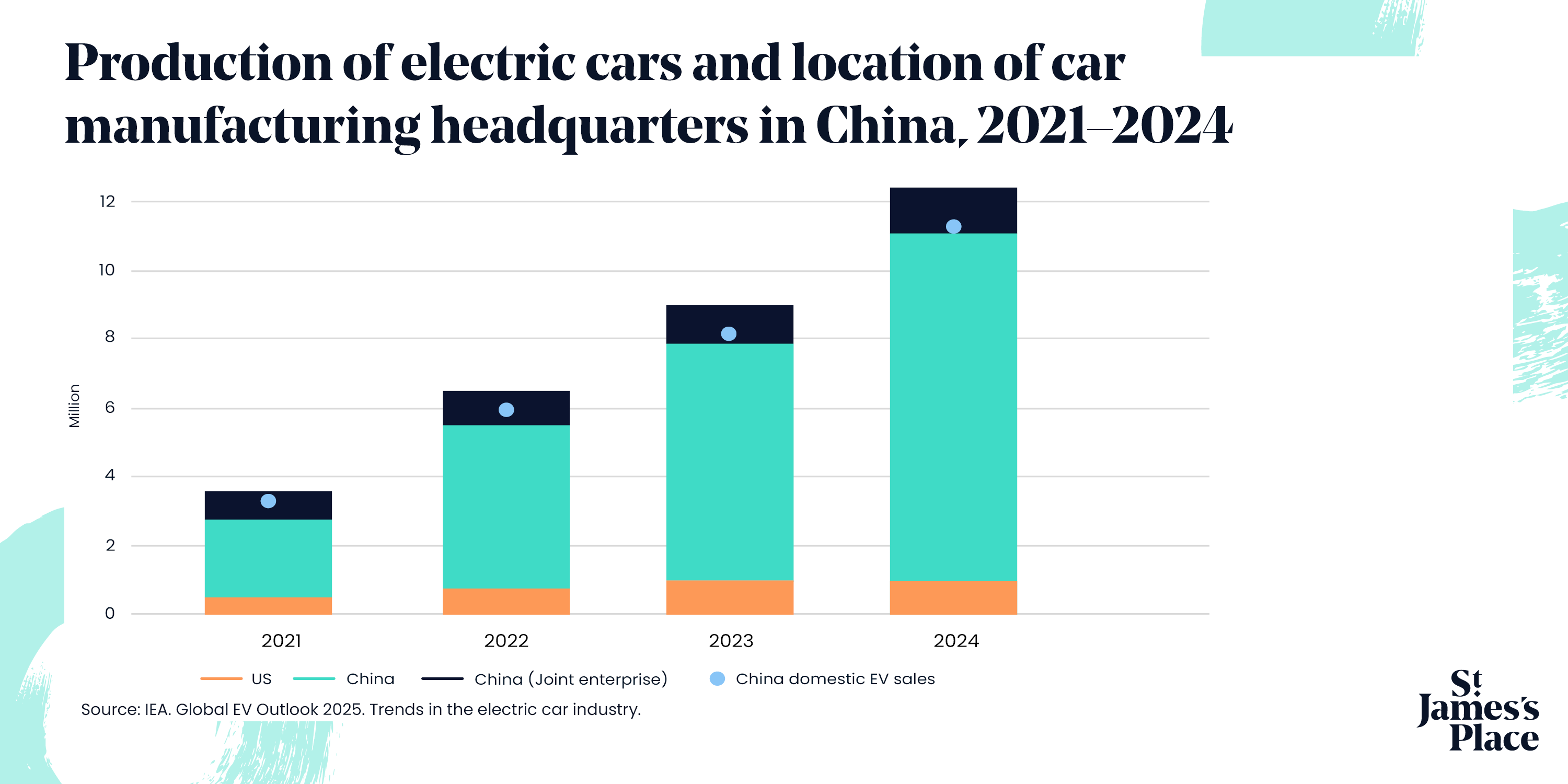

Dominating electric vehicle production – making it look easy3

- China has rapidly come to dominate global production of electric vehicles as the above chart shows. This has been driven by a desire to move away from the country’s dependency on imports to meet oil requirements (it relies on imports for almost three-quarters of its oil needs). During the first decade of the 2000s, a government strategy evolved to reduce the country’s dependency on oil.

- Domestic power sources were developed, supported by subsidies and tax breaks. These included coal, nuclear power, as well as solar and wind.

- Electrification was a central ambition. A key to China’s current domination of electric vehicles was the awareness that it needed control over electric vehicle (EV) batteries. Helped by its investment in the mining and refinement of many minerals, Chinese EV battery manufacturers have a major cost advantage over rivals in the west.

- China’s long-held manufacturing expertise and large domestic consumer market provides it with economies of scale unmatched elsewhere. This has allowed it to export and sell EVs at lower prices than similarly equipped cars from western car makers, even accounting for higher tariffs.

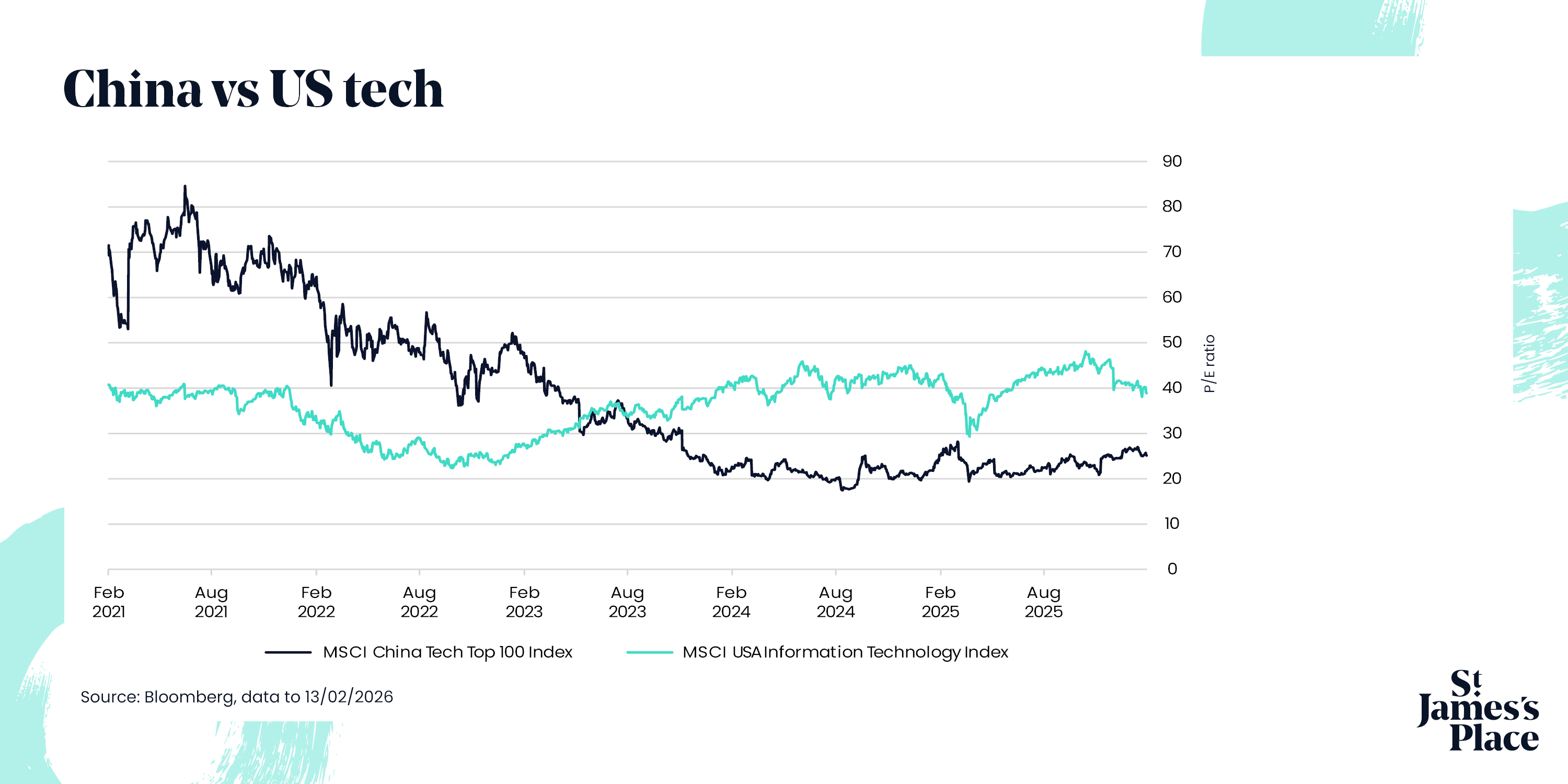

Why China tech is cheaper4

- Despite the recent sell-off for many US tech companies, they continue to trade at a significant premium compared to those in China.

- Many international investors apply a valuation discount to Chinese companies. to account for geopolitical and other risks. A notable concern is “involution”, the name for Chinese companies competing intensely with each other for very small, shrinking returns.

- The launch of China’s homegrown and lower development cost “Deepseek” AI model in mid-2025 sent shockwaves throughout the AI sector. Yet many investors believe this type of lower cost, lower-priced technology deserves a discount to its US peers.

- Some investors see Chinese tech companies as a relative “value play”, compared to its competitors elsewhere. With China’s leadership prioritising AI and pushing for a comprehensive national AI strategy, the domestic AI sector is expected to be a fast-growing support for national growth.

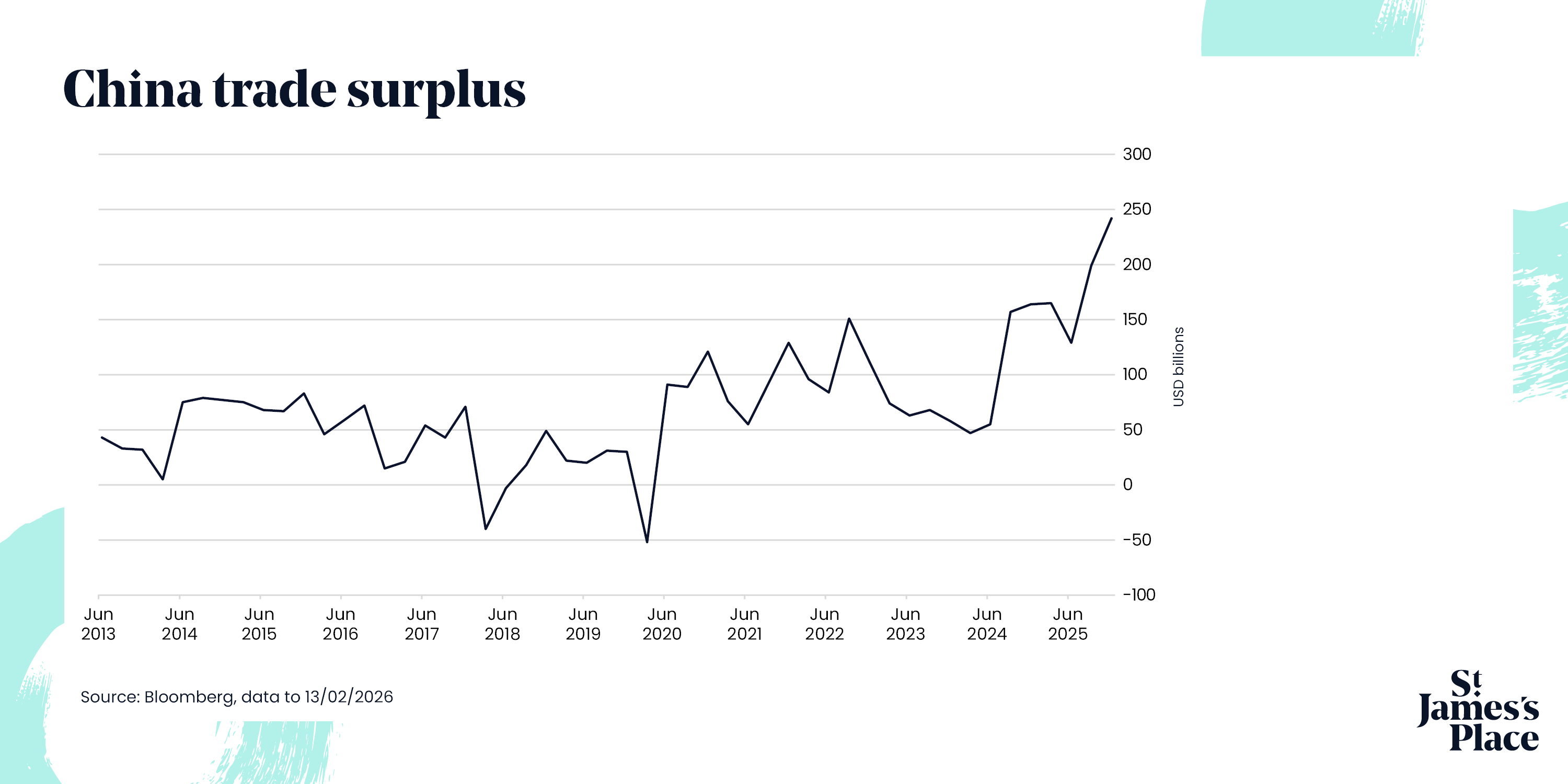

Trade surplus – the only way is up5

- Since the pandemic induced shutdown at the beginning of the decade, China’s current account trade surplus (more exports than imports) has increased dramatically. Recent tariffs have proved a notable but only temporary set-b.

- A major driver has been China’s successful transition up the manufacturing value chain. Good-bye cheap electricals and low value-added clothing, replaced by higher margin products such as EV cars and batteries.

- Higher levels of exports contrast with a more subdued domestic picture. A government drive for self-sufficiency has shrunk demand for foodstuffs such as corn and what. Coal, steel and iron ore imports have also slowed. This has helped to reinforce the size of China’s surplus position.

- China’s leadership is focused on a “dual economy” strategy. This means encouraging domestic self-reliance, so the Chinese state and companies are not reliant on external demand. Simultaneously, China is prioritising the rapid growth of high value-added products.

Any opinions expressed are those of SJP and are subject to change at any time due to changes in market or economic conditions. This material is not intended to be relied upon as a forecast, research, or investment advice, and is not a recommendation, offer or solicitation to buy or sell any securities or to adopt any strategy.

BLOOMBERG®” and the Bloomberg indices listed herein (the “Indices”) are service marks of Bloomberg Finance L.P. and its affiliates, including Bloomberg Index Services Limited (“BISL”), the administrator of the Indices (collectively, “Bloomberg”) and have been licensed for use for certain purposes by the distributor hereof (the “Licensee”). Bloomberg is not affiliated with Licensee, and Bloomberg does not approve, endorse, review, or recommend the financial products named herein (the “Products”). Bloomberg does not guarantee the timeliness, accuracy, or completeness of any data or information relating to the Products.

Certain information contained herein, including without limitation text, data, graphs, charts (collectively, the “Information”) is the copyrighted, trade secret, trademarked and/or proprietary property of MSCI Inc. or its subsidiaries (collectively, “MSCI”), or MSCI’s licensors, direct or indirect suppliers or any third party involved in making or compiling any Information (collectively, with MSCI, the “Information Providers”), is provided for informational purposes only, and may not be modified, reverse-engineered, reproduced, resold or redisseminated in whole or in part, without prior written consent.

Sources

1Macrobond 01/01/2026. Accessed 16/2/2026

2Bank of International Settlements. Accessed 13/2/2026

3IEA

4Bloomberg. Data to 15/2/2026. Accessed 16/2/2026

5Bloomberg. Data to 15/2/2026. Accessed 16/2/2026

Most recent articles